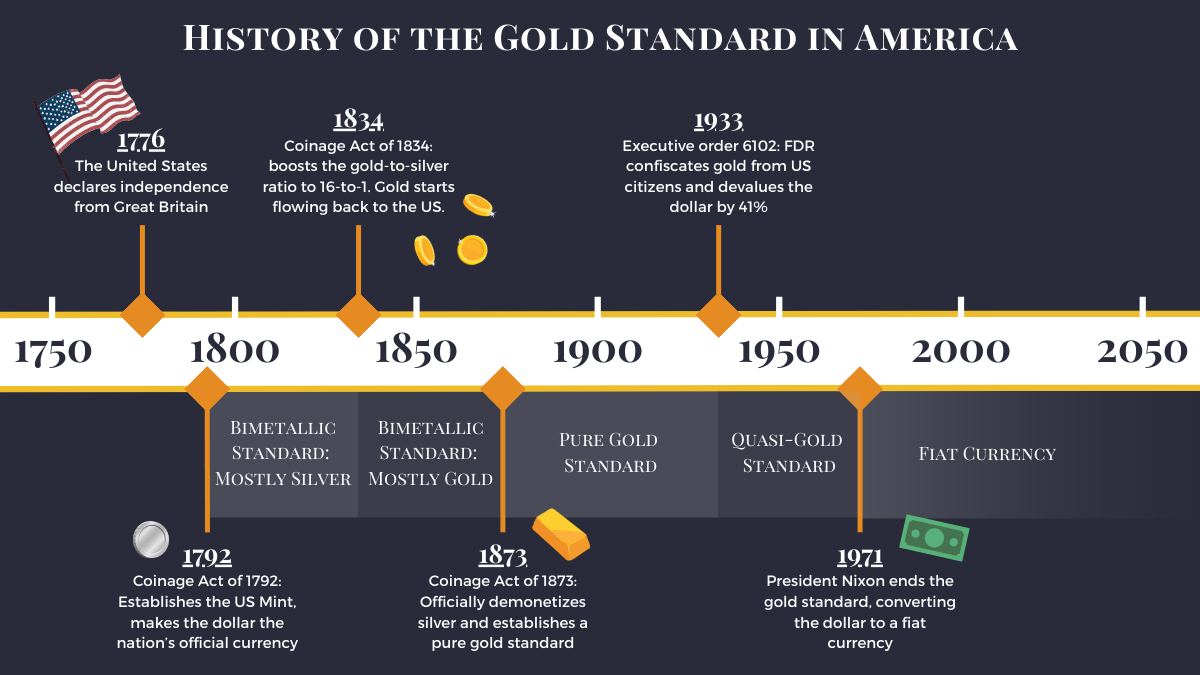

To understand the history of US monetary system, we must grasp the role of its central protagonist: gold.

For its first 200 years as an independent nation, America functioned on some version of a metallic standard. From 1792 to 1834, silver served as the primary backing. In 1834, the U.S. began transitioning to a gold standard, which became official with the demonetization of silver in 1873.

The US gold standard operated in its purest form throughout the late-19th and early 20th centuries, until FDR confiscated all privately held gold in 1933.

From 1933 to 1971, the U.S. remained on a quasi-gold standard, until President Nixon officially converted the US dollar into a fiat currency.

What is the Gold Standard?

The gold standard is a way for a government to ensure the value of its currency by linking it to gold.

The government agrees to convert each unit of currency for a specific weight of physical gold (say, 1/20 of an ounce), thereby giving paper money the same intrinsic value as gold. The government needs to hold large gold reserves to maintain public confidence and ensure that the currency can be converted into gold on demand.

Of course, “gold standard” also refers to something that is the best or most prestigious of its type.

There is little doubt that the United States’ gold standard played a pivotal role in its emergence as a world power. Yet, it was eventually replaced by a fiat system. The rest of this article will explore major shifts in the US monetary system throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

Beginning of the US Gold Standard: The Coinage Acts

In the sixteen years following America’s independence from Great Britain, Americans primarily used foreign coins, such as the Spanish silver dollar, as currency. In 1792, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton launched the first Coinage Act, unifying the US financial system.

The Coinage Act of 1792 established the United States Mint, which produced, circulated, and regulated coinage in the United States. The act also made the U.S. dollar the nation’s official unit of money. The gold-to-silver ratio was set at 15-to-1, meaning one ounce of gold was valued at 15 times one ounce of silver.

At the time, international markets valued gold at a higher rate (approximately 15½-to-1) against silver. This encouraged U.S. citizens to export their gold overseas. Gold started disappearing from U.S. circulation, leaving silver coins as the primary unit of exchange.

Congress Creates a Gold-Backed Dollar

To remedy this problem, Congress passed the Coinage Act of 1834. This Coinage Act boosted the gold-to-silver ratio to 16-to-1. Gold started flowing back to the U.S. while silver started flowing out. The California Gold Rush also increased the supply of domestic gold. This effectively pushed the United States onto a gold standard, though the nation still technically functioned on the bimetallic standard.

During this period, Americans did use paper currency such as banknotes and Treasury Notes. Every piece of paper represented direct convertibility to physical gold or silver.

Flirting with Fiat

On April 12, 1861, the Confederate Army attacked South Carolina’s Fort Sumter, officially beginning the US Civil War.

At first, the government tried issuing gold-backed Treasury Notes to fund the war. However, expenses soon surpassed the value of precious metals in America’s coffers, which forced the government to issue its first fiat currency: the greenback.

Fiat money, like the dollar bills we use today, has no intrinsic value. The US government declared greenbacks as legal tender, which encouraged citizens to use them in everyday transactions. Without restrictions on money creation, the government soon cranked up the money printer.

As greenbacks flooded the economy, inflation took hold. The greenback’s market value deteriorated quickly, forcing the government to remove greenbacks from circulation and reinstate the bimetallic standard. In the decade following the Civil War, the United States returned to gold and silver-backed money.

The International Gold Standard

In 1871, Germany replaced its multiple silver-based currencies with a unified gold backing. France, Belgium, Italy, Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, and Japan quickly followed suit, marking the beginning of the international gold standard.

US President Ulysses S. Grant officially demonetized silver with the Coinage Act of 1873, which ended the bimetallic standard. The “Crime of 1873,” as it is now known, sharply decreased the money supply in the United States.

Until the devastating impact of WWI, nearly all Western nations (as well as many nations in Latin America and Asia) kept their currencies pegged to gold.

Every currency was linked to every other currency at a fixed exchange rate, which made international trade extremely efficient. Gold served as the bedrock for economic value across the entire developed world.

The Gilded Age

From 1873 to 1933, the US gold standard operated in its purest form. Every piece of paper currency (such as gold certificates and Treasury Notes) could be exchanged for physical gold on demand. During this period, economic growth in America was nothing short of miraculous.

The late 19th century is known as the Gilded Age, during which U.S. industrial output skyrocketed. John D. Rockefeller, Thomas Edison, Andrew Carnegie, and J.P. Morgan created their famous monopolies, and the United States transitioned into a legitimate world power.

Labor conditions also began to drastically improve for working-class Americans. Since the Industrial Revolution began in the late 18th century, blue-collar workers had suffered health risks, long hours, and low wages. During the Gilded Age, factory conditions improved, child labor decreased, and wages increased. The middle class climbed to a new level of prosperity.

There were plenty of setbacks, such as the “Long Depression” of 1873–1879 and the Panic of 1884. However, these financial calamities paled in comparison to the Great Depression.

It is difficult to find a period during which Americans experienced such unprecedented growth in living standards.

The Golden Age of Invention

The miracle of the late 19th/early 20th century was not just limited to improvements in labor conditions. The scale of innovation under the gold standard was also extraordinary.

The telephone, airplane, and internal combustion engine all popped up in the United States during this period. Kerosene lamps turned into electric light bulbs. Horse-drawn carriages turned into cars, trains, and trolleys. Agricultural technology released millions of farmers from the burden of manual labor.

Electricity, plumbing, medicine, factory production, and infrastructure were all transformed during the Golden Age of Invention. Just look at this resume!

American Innovations:

- Internal combustion engine (George Brayton – 1872)

- Barbed wire (Joseph Glidden – 1874)

- Telephone (Alexander Graham Bell – 1876)

- Light bulb (Thomas Edison – 1878)

- Coca-Cola (John Stith Pemberton – 1886)

- Alternating current motor (Nikola Tesla – 1888)

- Kodak camera (George Eastman – 1888)

- Airplane (Orville and Wilbur Wright – 1903)

- Theory of Relativity (Albert Einstein – 1905)

- Sonar (Lewis Nixon – 1906)

- Synthetic plastic (Leo Baekeland – 1907)

- Television (Philo Taylor Farnsworth – 1927)

- Penicillin (Alexander Fleming – 1928)

European Innovations:

- Steam turbine (Charles Parsons, Irish – 1884)

- Automobile (Carl Friedrich Benz, German – 1885)

- Radar (Heinrich Hertz, German – 1887)

- Motion-picture camera (Auguste and Louis Lumière, French – 1895)

- Radio (Guglielmo Marconi, Italian – 1895)

Modern Americans should strive to replicate the environment that allowed such miraculous progress, stability, and growth to flourish. Some would say the gold standard played a big role in America’s success in this period.

The government had strict restrictions on money printing, which kept inflation in check and prevented top-down manipulation of the economy. Taxes were low, which allowed economic participants to plug their wealth back into the economy and incentivize entrepreneurs. The gold standard stabalized exchange rates, facilitating international trade and giving domestic producers access to cheaper and higher quality raw materials.

Unfortunately, the catastrophes of the 20th century were just around the corner.

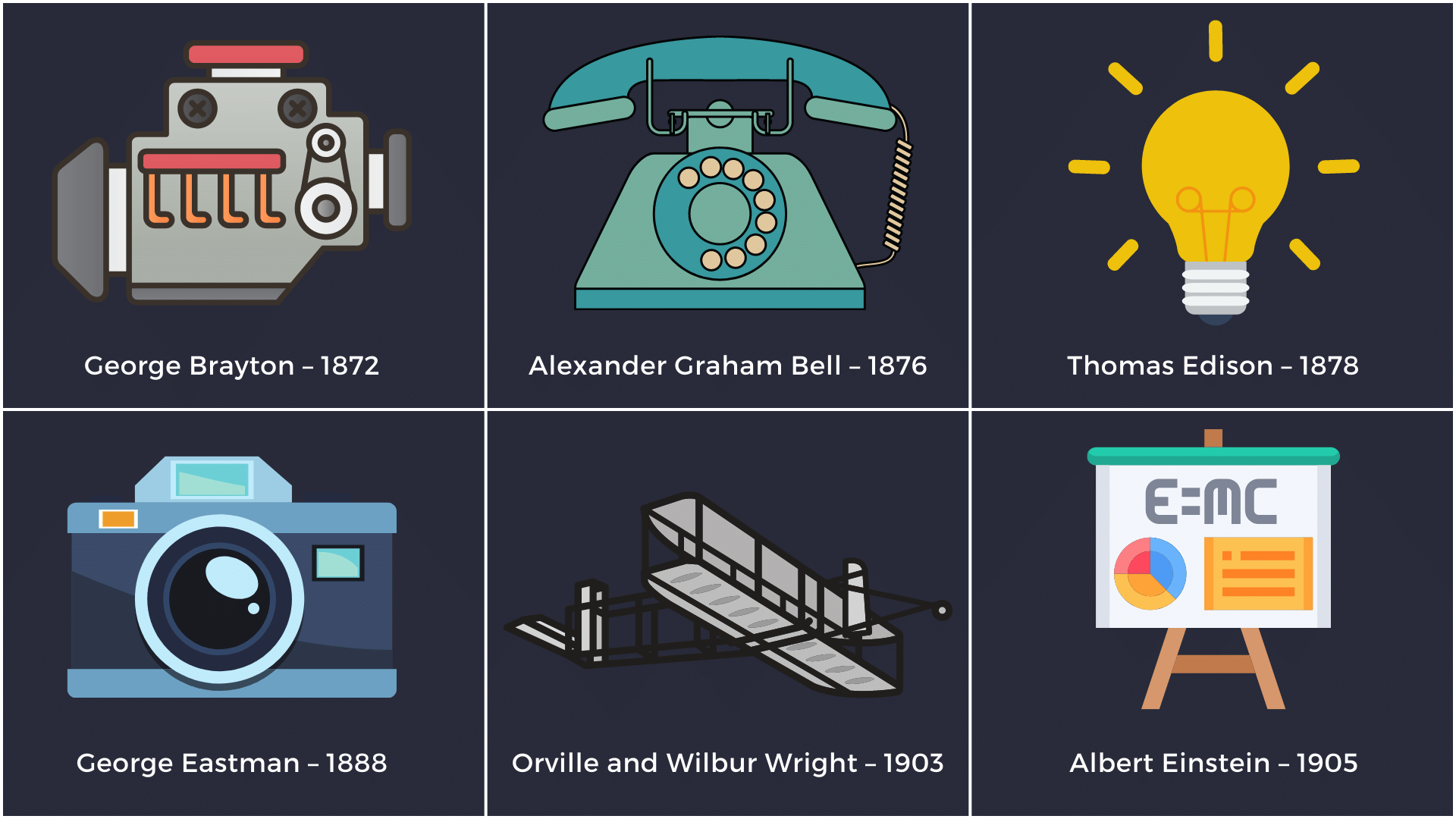

The Roaring Twenties and Great Depression

Economists have differing opinions on the causes of the Great Depression. Supporters of the gold standard blame the Federal Reserve’s reckless policies throughout the 1920s and 30s. In their view, the gold standard could have prevented the disaster, but the government and banking system found loopholes that allowed them to expand the money supply, creating a massive financial bubble and subsequent crash.

Critics of the gold standard claim the gold standard prevented the government from responding appropriately to the crisis. The gold standard intentionally places limits on credit creation and money printing, which prevents governments from handing out cash during depressions.

In his 1963 book America’s Great Depression, economist and historian Murray Rothbard tracks the increase in money supply during the Roaring Twenties. The Federal Reserve System helped increase the money supply from $45.3 billion in 1921 to $73.26 billion in 1929. The money supply increased 61.8% ($28 billion), while U.S. gold reserves only increased by $1.16 billion.

In his calculation of the money supply, Rothbard includes physical currency as well as “money substitutes” such as demand deposits, time deposits, savings and loan capital, and life insurance reserves. This is similar to the way we calculate M2 money supply today. The supply of physical currency did not increase dramatically, but the supply of credit did.

Was the Depression the Fed’s Fault?

The Federal Reserve was originally formed in 1913 to serve as an emergency lender for banks. If a bank ran out of money, it could take out a loan from the Fed. The bank had to pay interest on this loan: the discount rate.

For its first decade of existence, the Fed kept the discount rate relatively high, discouraging banks from borrowing excessively. However, in the mid-1920s, the Federal Reserve shifted toward a policy of “continuous credit,” which allowed commercial banks to borrow as much money as they wanted at a very low discount rate.

According to a 1923 Federal Reserve report: “The Federal Reserve banks are the country’s supplementary reservoir of credit and currency, the source to which the member banks turn when the demands of the business community have outrun their own unaided resources. The Federal Reserve supplies the needed additions to credit in times of business expansion and takes up the slack in times of business recession.”

This marked a fundamental shift in central banking. The Fed was no longer an emergency backstop, but an arbiter of credit creation and economic growth. The Fed lowered effective reserve requirements, which allowed banks to lend out more money for every dollar they held in reserve.

Consumers began buying big-ticket items, such as automobiles, with borrowed money. Investors took on debt to speculate on the soaring stock market, using their stock as collateral. The stock market skyrocketed by 376% from 1921 to 1929.

Eventually, the Fed decided to put on the breaks. They raised interest rates and popped the speculative bubble. The ensuing crisis would go down in history. People rushed to withdraw all their money from banks. Companies went bankrupt. Millions of people lost their jobs. It would take 25 years for the stock market to reach its 1929 peak.

How FDR Suspended the US Gold Standard

As the Great Depression ravaged the nation, many policymakers felt the need to expand the money supply and stimulate the economy. Only one thing stood in their way: the gold standard. The gold standard put a strict limit on money printing, which kept the Fed from engaging in expansionary policies.

On April 5, 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6102, which made private gold ownership illegal. All Americans had to sell their gold bullion and coins to the government at a price of $20.67 per ounce. Those caught “hoarding gold” faced up to 10 years in prison.

Immediately after confiscating the gold, FDR raised the price of gold to $35/ounce. This drastically increased the value of the government’s gold assets, allowing them to increase the money supply. The move devalued the U.S. dollar by 41%.

After 1933, gold still technically backed the U.S. dollar, but the connection had been severed for everyday citizens. For better or worse, U.S. monetary system would never be the same.

Bretton Woods: The Gold Exchange Standard

In 1939, Europe plunged into the Second World War. For six years, the Allied and Axis powers battled across every corner of the globe, killing millions in the process.

By 1945, nearly every financial system, population, and landscape in the developed world had been decimated. After the war, the United States held a conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire to lay the groundwork for a new international monetary system. Delegates from forty-four nations helped construct the agreement. Because the U.S. economy had emerged relatively unscathed from the war (at least compared to Europe), and because the US held three-fourths of the world’s gold supply, the delegation chose the U.S. dollar as the international reserve currency.

All currencies were pegged to the dollar, which was pegged to gold. In exchange for this massive economic advantage, the United States took on the responsibility of keeping the world’s oceans safe, facilitating global free trade, and serving as the world’s policemen.

The Bretton Woods agreement also established the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, which continue to play a significant role in the global economy today.

Why President Nixon Ended the Gold Standard

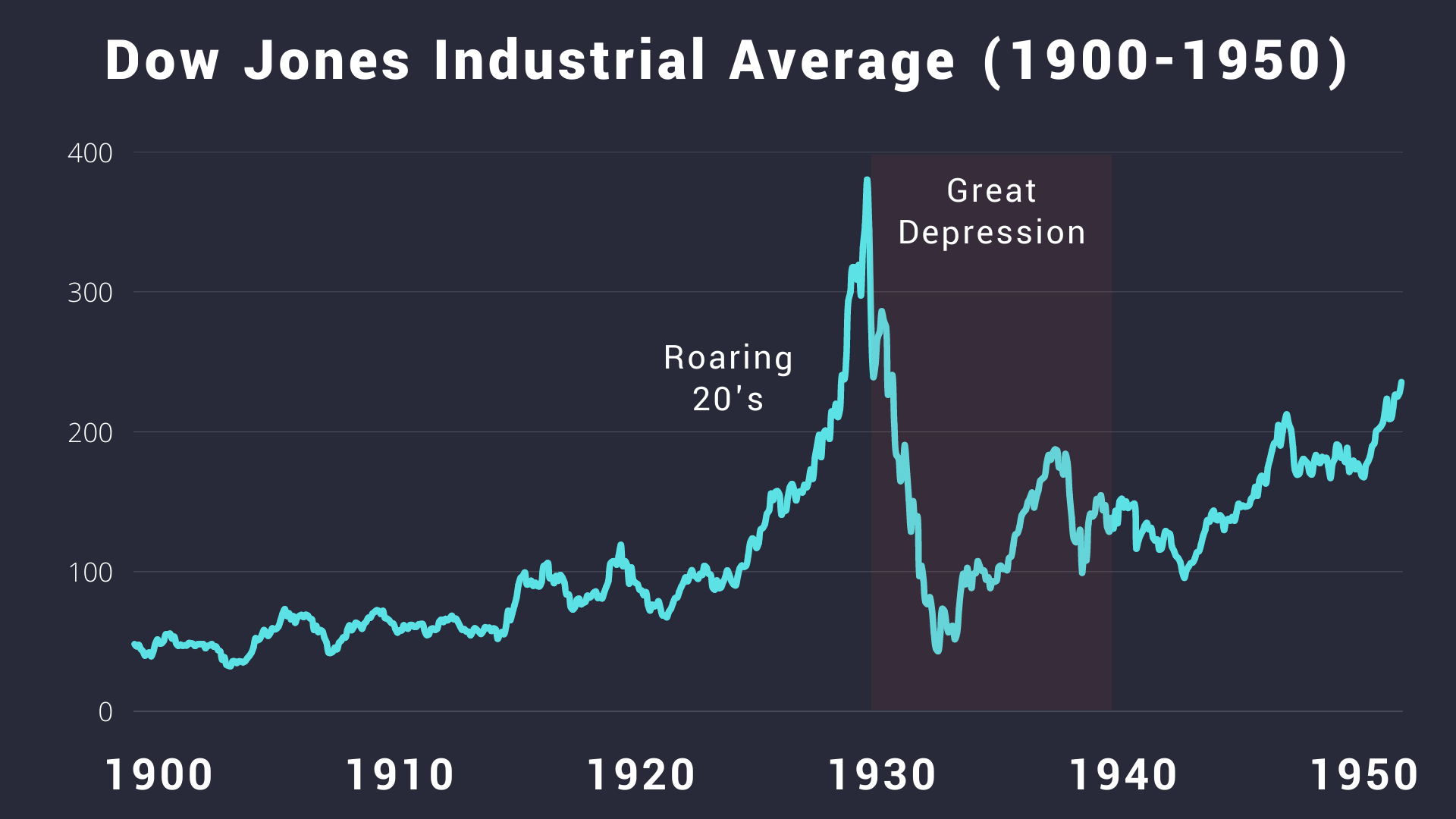

The US enjoyed the advantages that came with being the world’s undisputed military and economic power. Throughout the 1960s, the U.S. dished out dollars to fund the Vietnam War and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs.

As the supply of dollars ballooned, other nations began to doubt the US government’s ability to exchange their dollars for gold at the agreed-upon exchange rate of $35 per ounce. In the mid-1960’s, France began aggressively exchanging their official dollar reserves for gold, quickly draining U.S. gold reserves. On August 15th, 1971, Richard Nixon suspended gold convertibility and struck the final nail into the coffin of the gold standard.

All major currencies transitioned to a floating exchange rate system. Governments could now print money to their hearts’ content.

The Petrodollar: Backed by Oil?

After the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, the US struggled to maintain global trust in its currency. To remedy the problem, Nixon took aim at a new commodity: oil.

Following the 1973 OPEC oil crisis, the US reached a strategic agreement with Saudi Arabia (the world’s largest oil producer at the time). The agreement stipulated that Saudi Arabia would price and sell their oil exclusively in US dollars in return for military protection. By 1975, all OPEC members agreed to trade oil in US dollars.

The petrodollar system required countries around the world to hold significant reserves of US dollars to engage in international trade, particularly for purchasing oil.

The Great Inflation

The petrodollar system succeeded in deepening US capital markets and giving the US a privileged postion in global trade. However, the end of the gold standard still marked the beginning of the painful Great Inflation.

Between 1971 and 1980, economic growth stalled, inflation surged, and stocks struggled. Inflation peaked at 14.76% in 1980.

During this period, the price of gold surged from $35/ounce to $875/ounce. Even though the U.S. dollar no longer had a connection to gold, an increase in the gold price still represented a collapse in the value of the U.S. dollar. That dynamic remains to this day.

In 1980, Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker ended the Great Inflation by cranking up interest rates to nearly 20%. This triggered two recessions but succeeded in stabilizing the dollar.

What Backs the US Dollar Today?

Since Nixon severed the gold standard, the U.S. dollar has functioned as a fiat currency. Some would say “functioned” is a strong word, given how much the dollar’s value has plummeted since 1971. Fiat currencies have no intrinsic value, relying instead on policymakers to preserve the currency’s purchasing power.

The question “what backs the US dollar?” is now a difficult one to answer. Is it the “full faith and credit of the US government”? “Trust”? The “strength of the US economy”?

If you would like to explore this question further, check out this article: What Backs the United States Dollar?

Since the end of the gold standard, federal debt has skyrocketed, wages have stagnated, wealth inequality has increased, the cost of living has soared, and savings rates have declined. Each of these secular trends took a noticeable turn in the 1970s, which indicates they may stem from the government’s monopoly on money.

However, we must be careful not to oversimplify these issues. Plenty of positive trends have occurred since the 1970s as well, such as a drastic decrease in the number of people living in extreme poverty (most of this progress has occurred in Asia).

Gold’s Role Today

On December 31st, 1974, Gerald Ford repealed FDR’s restrictions on private gold ownership. Since then, investors have purchased physical gold to capitalize on dollar devaluation. Individuals have very little control over the monetary system, but they can replicate some of the economic advantages of the gold standard in their personal portfolios.

Gold has maintained its purchasing power for over 5,000 years, and will continue doing so. Central banks still hold a significant percentage of their assets in gold. The gold standard is gone, yet the world’s leading central bankers continue to demonstrate their commitment to the idea that gold is money.

If you’re interested in doing the same, set up a Vaulted account or give us a call!